I have been reading a very interesting book,

The Unhappy Consciousness by

Sudipta Kaviraj, an Indian political historian from Bengal.(Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995). In fact, I have only been reading and rereading the book's third chapter which is called "The Myth of Praxis: Construction of the Figure of Krishna in the

Krishna-charitra."

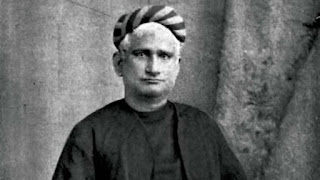

Now I know that I have mentioned Bankim Chandra and his reevaluation of Krishna's life before.

Bankim was Bhaktivinoda Thakur's slightly younger contemporary and though he became far more influential in India than the Thakur, they shared one common interest: the direction of religion in Bengal and India and Krishna's place in it. Bhaktivinoda wrote

Krishna-samhita in 1880 and Bankim wrote

Krishna-charitra in 1886. It is hard to imagine that there was not some common link between these two books, though again, Bankim's influence was more widespread, with Aurobindo and Vivekananda being at least two major figures who were influenced by his views. Even today, with the worldwide spread of Krishna consciousness that Bhaktivinoda Thakur set into motion, it is safe to say that in the land of his origin, he is not seen as much more than a sectarian thinker, and Chaitanya Vaishnavism still occupies a somewhat marginal position in wider Bengali society. This was quite obvious to me the last time I visited Calcutta.

Shukavak N. Das's book about Bhaktivinoda Thakur's

adhunika vada is something that has come up directly or indirectly over the years and is still an obvious point of contention in IGM circles, and as

this article by Krishna-kirti shows, even accredited devotee academics find it a particularly difficult stumbling block. But on reading this article by Prof. Kaviraj, I have come to see that my own way of thinking has in some significant ways come to meet Bankim's, who seems to have been asking the same questions as Bhaktivinoda, but going more deeply into many of them. I say this even though in principle I find that he may have been hampered by an inadequate understanding of Rupa Goswami's philosophy--as is Prof. Kaviraj himself. The problem Bankim was really addressing was "What kind of religion does Bengal need today?"

Prof. Kaviraj has revisited Bankim Chandra's particular point of view, not only summarizing and analyzing his reasoning and underlying purpose, but also supplying a great deal of context and depth of comprehension. It is helping me to clarify where I stand in relation to many of the metaphysical questions related to issues like God, avatar and Krishna.

This article is very rich in content and it will be difficult to summarize its 33 pages concisely, so I heartily recommend everyone read it in full. As I have said before, I feel particularly connected to Bhaktivinoda Thakur's two-edged project: one of establishing a rational base for Krishna bhakti, and second to make Radha-dasya the single goal of my religious life. I read Krishna-samhita in Bengali many years ago, but its significance was lost on me until I read Shukavak's book. Similarly, I read Krishna-charita in Bengali many years ago, but Prof. Kaviraj's article has made it much clearer to me the extent of Bankim Chandra's argument--with the help of a hundred years of hindsight.

This is the end of my preamble. I decided to just post a section of an article I wrote a long time ago when I first started my B.A. in religious studies that summarizes a kind of general formative idea about Bankim that I've had up until now. It still pretty much stands, and for those not familiar, it will give a basis to understanding Bankim's argument and the discussion of Kaviraj's essay a little more fully.

----------------------

First European travellers to India had an extremely negative opinion of Vaishnavism. Nineteenth century British descriptions of Vaishnava sahajiya gurus in the yearly festival at Ghosh Para (near present day Kalyani in Nadia) distastefully paint a picture of them surrounded by bands of admiring females. The association of sexuality with religion in any form was anathema to 19th century Protestantism and it was not long before this revulsion found a counterpart in Bengal. Ram Mohan Ray, the father of the Bengal Renaissance, found absolutely nothing redeeming about Vaishnavism, which he considered to be a corruption of the true Upanishadic religion, perceived by him to be a type of Unitarianism. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, on the other hand, attempted to reform Vaishnavism by salvaging the reputation of the much maligned avatara and speaker of the Bhagavad gita, Krishna.

The work in which Bankim discussed the personality of Krishna and which had a great impact was Sri Krishna charita. In writing this book, Bankim’s goal was similar to that of his contemporary, Syed Amir Ali, an apologist to the world of probing, prying Western Orientalists who were calumniating the character of the Prophet. Two of the most damaging criticisms levied at both Muhammad and Krishna were that they did not preach Christian non violence and that their sexual mores were questionable, neither of them being monogamous. Both the Qur’an and the Gita condone the principle of the holy war, jihad and dharma yuddha respectively. It is important to remember that in the struggle for Indian independence there could be no better ideological tool for nationalists than such a doctrine and so both apologists justified it without reservation. On the other hand, the apparent sensuality of these religious founders (in contrast to the example of Christ) was an apparent paradox which needed some explaining away.

Bankim in particular sought to do so by a guarded exercise of demythologization: using the critical method of the Orientalists, he peeled away the mythological layers to discover three distinct Krishnas. The outermost layer was the Krishna of the Bhagavata who played with the gopis, whom Bankim argued was a later, fictional accretion to the original historical personality of Krishna. The popularity of this purely mythological Krishna was to be blamed on Chaitanya. Bankim detested the effeminacy which had overcome the Vaishnavas in their following of the purely mythical Krishna; especially distasteful to him was that aspect of Tantric sahajiyaism which promoted a type of devotional quietism centred around a sexual ritual based on the characters of Krishna and his consort Radha. Though he avowed that the Vaishnavism taught by Chaitanya may have been of benefit to a few highly elevated souls, its misuses brought one into a degraded type of debauchery. The other Krishnas were another mythologized figure, the warrior hero of the Mahabharata and incarnation of Vishnu, and the historical Krishna, who though cut down to human proportions, was defended not only as being historically real, but as perhaps the greatest person in Indian history.

Bankim followed the positivist influence of Comte in recognizing the people’s need for gods and, in his desire to reshape Hinduism into a new nationalistic religion, he reenlisted the ‘real’ Krishna for the generalship of the new battle for cultural identity. This was the political figure, the Krishna of Kurukshetra, a much more heroic ideal who responded most perfectly to this concept of the type of god necessary to meet the needs of the age, a symbol more fit to shape the Hindu character than the other Krishna of Vrindavana, the dhira lalita so beloved of Chaitanya; this, in spite of the warrior Krishna’s being considered a lower form of the Supreme in Chaitanyaite theology. Bankim felt that the humbling of the Bengali race as a viable political force was due simply to the vitiation of the original, heroic religion that Krishna had preached. Thus, though Bankim’s ultimate conclusion was that the historical Krishna is not as important as the philosophy which goes in his name, as the original speaker of that philosophy, the founder of that ‘beautiful religion which is against the Mimansakas “this superior religion’, he was worthy of the appellation avatara.

Like Syed Amir Ali with his revamped Islamic pride in a Prophet who was also a man of the world, Bankim took pride in Krishna’s political achievements. He felt Buddha and Jesus to be less worthy of reverence precisely because they were renouncers and thus misleaders.

As a result of this this worldly attitude, Bankim did not care much for Ramakrishna Paramahamsa either, though he was interested enough in him to pay him a visit on at least one occasion. He considered Ramakrishna to be in the same class as the other saànyasins and therefore felt that his preaching was detrimental, leading people to follow an otherworldly, mystical path which did not meet the needs of the hour.

Ramakrishna’s disciple, Vivekananda, on the other hand, followed Bankim’s lead in calling out for the Kurukshetra Krishna and Aurobindo also, recognizing the call, naturally followed. This heroic call to a this worldly renunciation was often interpreted as a call to the rajo guna, a call to action. The devotional elaborations of all the varying otherworldly mystics, whether yogi or Vaishnava, were all considered to lead to the tamo guna, the mode of ignorance or lethargy, despite their heady claims of higher levels of consciousness. Aurobindo paraphrases Vivekananda in the following call to revolution: "We need the mode of passion! We need the heroes of the work force in this country! Let them float in the forceful currents of Nature. On that account, even if sin should befall us, it will be a thousand times better than this ignorant lassitude of tamo guna."

It is not surprising, therefore, when we find that Aurobindo credits Bankim Chandra for being the one who "first gave to the Gita this new sense of a Gospel of Duty."

The revival of the karma yoga ideal was perhaps a natural development in a society coming under the influence of an imperial Western culture in the heady days of early industrialism with faith in its work ethic ideology at an apex. At any rate, the Hindu reformation Weltanschauung of the 19th century was decidedly against the erotic love symbolism of Chaitanya Vaishnavism.

This essay then went into a further discussion of the influences that this discourse had on Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati and the Gaudiya Math, and subsequently on Iskcon. The basic premise is that Bankim successfully changed the terms of a discourse and moved the doctrinal center to a place away from the "erotic" to the "heroic."

I have another old essay from Gaudya Discussions that I will repost,

"Who Genuinely Represents Chaitanya Mahaprabhu?" for the record and for anyone interested in pursuing these matters and for background.

Comments

this was said in public in front of many people . needless to say , bankim would not give anymore importance to ramakrishna than a petty sannyasi !

in bankims ancestral viilage house which has now been converted to a museum , there hangs paintings of all major bengal rennaisance figures except ramakrishna and vivekananda . when i asked the reason , i was shown the incident in kathamrita by the curator .

secondly i refuse to admit that vivekananda was influenced by bankim . while talking about bengal and its literature he openly criticized the state of bengali literature , for being overloaded with romantic novels and fictional stories(something which bankim speicallized in) . in those days novel and bankim were synonymous words !

vivekananda called upon authors to write informative books for public instead of useless storybooks which did no practical good .

vivekananda also wrote in chalit bangla or the common spoken bengali rather than the ornate sanskritised bengali in use at that time . he also said that literature should follow the

spoken speech of the masses if it wants to grow and sustain itself .

bankim's literature on the other hand contains the most heavy sanskritisations ever produced in bengal .

it is hard to imagine that this same vivekananda would take inspiration from bankim .

well i would disagree with two point the author makes in some places . personally im a follower of ramakrishna-vivekananda-chaitanya thought .

i totally accept the chaitanyaite philosophy which places vraja leela at the highest stage , and not just out of emotionalism .

krishna exemplifies bhakti and prema which in turn finds its highest expression in parakiya rasa as shown by the gopis . for any true sadhak there can never be any other better ideal than craving for this prema towards god .

however i also agree that vaishnva teachings have kept aside the 'heroic krishna' for so long that people have almost forgotten than krishna can fight a war . in eyes of modern people krishna never seems to leave his flute or the side of gopis . this is something that needs to be changed .

hinduism also needs to stand up and 'reinventing' the heroic krishna will actually help the purpose . bankim chandra chatterjee has done just that through his krishna charitra and anandamath .

however the disagreements that he had with ramakrishna paramahamsa was probably due to some other causes .

in ramakrishna kathamrita we find an anecdote about bankim's meeting with the paramahamsa . when asked by paramahamsa as to what are the goals of human life , he mentioned finding food , sleeping , and sexual life as its answer .

ramakrishna was disgusted at such and answer and said " yuck ! you belch of what you eat . you are such a big pandita , and to hear such words from your mouth ! a scavenger vulture can rise high up in the sky but his eyes remain fixed to the ground , searching for rotting carcass ! "

......[continued]

now , if one analysis history it would be very clear to him that what was erotic in victorian india was clearly not earotic in ancient india . geetagovindam was sung in brahmin courts without ever being stigmatised . notions of eroticism was completely different back then .

it is totally unjustified to dismiss the beauty of vaishnav padavali on the pretext of morals and eroticisms .